Overview

Republic Act 11469 was signed into law on 23 March 2020 (also known by its short title as the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act) declaring a national health emergency throughout the Philippines as a result of the COVID-19 situation. In it Congress authorizes the President to exercise the necessary special powers, for a limited time and subject to certain restrictions, to address a problem that poses a clear and present danger to the people.

This Primer provides only a simplification of the key provisions of the Act and is intended to encourage wider and popular discussion of the social and political issues surrounding the Philippine response to the COVID-19 emergency. The reader is encouraged to examine RA 11469 in its entirety as well as other related laws, especially the 1987 Constitution. The reader is also encouraged to exercise vigilance and reason by being better informed in the face of a health crisis emergency.

Questions

- What is the reason for the Act?

- Have there been other instances when a national health emergency has been declared in the Philippines in the past?

- Is this the first infectious disease to hit the Philippines?

- Is this the first time for a Philippine president to issue an emergency proclamation since 1987?

- Does the promulgation of the Act have a constitutional basis?

- Why can’t the president declare martial law instead to address this health emergency caused by COVID-19?

- Does the Act have a maximum effectivity period?

- What is the Act supposed to do?

- Who are PUIs and PUMs?

- What kind of standards and protocols does the Act provide for in preventing or suppressing the further spread of COVID-19 in the Philippines?

- Since this is a national health emergency, are health workers entitled to any benefits under the Act?

- What are the responsibilities of local governments under the Act?

- What can the general public expect from the temporary emergency powers of the President under the Act?

- Are there other special temporary powers given to the President under the Act?

- Does the Act allow the president to change anything in the 2020 national government budget?

- What happens to the other government-appropriated projects and programs that do not pertain to dealing with the COVID-19 emergency?

- Does the Act allow for donations of health products?

- To whom is the President accountable under the Act?

- Does the Act provide for an oversight mechanism?

- Can the Act supersede any existing law or regulation?

- Does the declaration of a health emergency invalidate the Constitution or any of its provisions?

- Does the Act punish those who violate its provisions?

- What offenses are punishable under the Act?

- Is spreading false information also an offense punishable under the Act?

- What constitutes the elements of chaos, panic, anarchy, fear, and confusion associated with spreading false information under the Act?

- Are my Constitutional rights still protected then?

01

What is the reason for the Act?

Congress promulgated the Act in view of the serious health threats and disruptions posed by COVID-19 on the lives and livelihoods of people and the economy as a whole (Section 2). In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020 has already characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic and called on all countries to take urgent and aggressive action to mitigate or prevent its spread.

The Act comes in the wake of initial measures already taken by the president to address the COVID-19 situation with the issuance of Proclamation 922 (signed 8 March 2020) declaring a state of public health emergency throughout the Philippines and Proclamation 929 (signed 16 March 2020) declaring a state of calamity throughout the Philippines and imposing an enhanced community quarantine throughout Luzon.

Back to Questions

02

Have there been other instances when a national health emergency has been declared in the Philippines in the past?

None. This is the first national health emergency powers legislated by Congress for the president to exercise at least since the adoption of the 1987 Constitution.

However, this is not the first time that Congress has granted special temporary emergency powers to the president and to the Executive Branch of government.

In 1991, Congress passed RA 6978 to allow for the acceleration of the construction of irrigation projects (over a ten-year period) on the part of the National Irrigation Administration (NIA) in view of the impending crisis facing the agricultural sector at the time.

Realizing that the country was in the midst of a power shortage, Congress passed the Electric Power Crisis Act of 1993 (RA 7648) authorizing then-President Fidel Ramos to enter into negotiated contracts for the construction, repair, rehabilitation, improvement or maintenance of power plants, projects and facilities subject to certain requirements. That Act also provided for the reorganization of the National Power Corporation (NAPOCOR). These would not have taken place under normal circumstances. This Act was effective for a period of one year only.

Congress also passed the National Water Crisis Act of 1995 (RA 8041) authorizing the government to address issues related to the water crisis. The law also created the Joint Executive-Legislative Water Crisis Commission.

In late December 1989, Congress promulgated RA 6826 declaring a state of national emergency throughout the Philippines and granted special emergency powers to then-President Corazon Aquino to allow her to carry out the task of economic reconstruction in the aftermath of the destruction caused by the mutiny and rebellion of certain elements of the AFP to seize power and take over the government (see RA 6826).

Under the 1935 Constitution, Congress (at the time, it was called the National Assembly) declared a state of total emergency and granted the president special emergency powers to then-President Manuel L. Quezon in December 1941 to promulgate whatever rules are necessary to address the war between the US and its enemies (see Commonwealth Act 671).

Back to Questions

03

Is this the first infectious disease to hit the Philippines?

No. Previously, there have been other infectious diseases that have reached the Philippines. However, COVID-19 is the most serious infectious disease that the country has faced in recent times with thousands of infections and over a hundred deaths to date and still growing.

In late 2019 the poliovirus was found in sewage samples in the Philippines. This caused a degree of concern for health authorities since it was thought that the poliovirus had been wiped out in the country. The last indigenous poliovirus infection recorded in the Philippines was in 1993. The issue was eventually addressed with a widespread campaign to vaccinate vulnerable segments of the population, notably children.

In mid-2015, the country was faced with another health issue with the outbreak of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) when one foreign national who arrived in the Philippines was found to be infected with it. The response of the Philippine government was to implement established protocols such as immediate treatment, testing, and contact tracing.

From late 2008 to early 2009 there was the problem of Ebola Reston when six slaughterhouse workers were found to be infected due to their daily contact with pigs.

Between 2004 and 2005, the country had a number of cases of meningococcal disease. In 2003, there was the severe acute respiratory syndrome or SARS that was, up to that time, the most serious health issue the Philippines had faced that reached a degree of local transmission.

Back to Questions

04

Is this the first time for a Philippine president to issue an emergency proclamation since 1987?

No. Several Presidents have issued their own emergency proclamations to address particular crisis situations.

In late May 2017, President Duterte issued Proclamation 216 placing the whole of Mindanao under martial law and suspending the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus in response to armed conflicts centered in Marawi city initiated by the Maute group aligned with the Islamic State. Martial law was allowed to lapse two and a half years later.

In early September 2016, President Duterte also issued Proclamation 55 declaring a state of emergency in the entire Philippines in response to the Davao City bombing that killed more than a dozen people. Unlike previous proclamations, Proclamation 55 does not enumerate the specific special powers that the president can exercise and has no fixed time frame as to its effectivity.

In February 2006, then-President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo issued Proclamation 1017 declaring a state of national emergency resulting from another coup attempt. The state of national emergency was lifted in early March 2006 by virtue of Proclamation 1021.

Proclamation 503 issued by then-President Corazon Aquino in early December 1989 declared a state of national emergency as a result of military adventurism and a coup attempt led by Col. Gringo Honasan that threatened the government at the time. This Proclamation eventually led to the granting of special powers to the president by way of RA 6826 (see above).

Back to Questions

05

Does the promulgation of the Act have a constitutional basis?

Yes. The temporary emergency powers of the President are constitutional when obtained by legislative enactment specifically to allow the Executive Branch of government to better address a particular threat facing the country and its people by means of a declared national policy. The 1987 Constitution provides that:

In times of war or other national emergencies, the Congress may, by law, authorize the President, for a limited period and subject to such restrictions as it may prescribe, to exercise powers necessary and proper to carry out a declared national policy. (Article VI Section 23)

Back to Questions

06

Why can’t the president declare martial law instead to address this health emergency caused by COVID-19?

Under Article VII Section 18, the President can declare martial law only for the purpose of suppressing lawless violence, invasion, or rebellion. Clearly, none of these conditions exists in the country under the current situation with the COVID-19 emergency.

The President has the power to call out the armed forces under the Constitution. However, the situation is one that requires a concerted and holistic approach to addressing a health emergency specific to the spread of an infectious disease in which health experts, local authorities, the private sector, and entire communities need to be involved. This is an area that the military may not be in a position to address by itself.

Back to Questions

07

Does the Act have a maximum effectivity period?

Yes. The Act specifies that it will be in full force and effect for a period of three months “unless extended by Congress” or “withdrawn sooner by means of a concurrent resolution of Congress or ended by Presidential Proclamation” (Section 9).

However, in the event that Congress decides to extend the effectivity of the Act, the 1987 Constitution provides that such emergency powers cannot go beyond “the next adjournment of Congress” (as prescribed in Article VI Section 23) which, in the case of the current 18th Congress, ends by 2023.

Back to Questions

08

What is the Act supposed to do?

The Act is directed at addressing the public health emergency caused by COVID-19. The ultimate goal is to protect and promote the welfare of the people. Section 3 of the Act enumerates the government’s specific goals as follows:

- mitigate and contain the transmission of COVID-19;

- immediately mobilize assistance for the provision of basic necessities to families and individuals affected by the enhanced community quarantine, especially the poor;

- undertake measures to prevent the overburdening of the country’s healthcare system;

- immediately provide ample healthcare, including medical tests and treatments, to COVID-19 patients, persons under investigation (PUIs) and persons under monitoring (PUMs);

- undertake a recovery and rehabilitation program as well as social amelioration program and other social safety nets to all affected sectors;

- ensure adequate, sufficient, and readily available funds to undertake the above-stated measures and programs;

- partner with the private sector and other stakeholders in the quick and efficient delivery of these measures and programs; and

- promote and protect the collective interests of all Filipinos.

Back to Questions

09

Who are PUIs and PUMs?

According to the Department of Health (DOH) assessment decision tool for COVID-19 (as of 26 February 2020), a person under investigation (PUI) is someone who exhibits any of the known symptoms of COVID-19 as prescribed by health authorities AND has had a history of travel to countries where there has been an outbreak of COVID-19 OR has come in close contact with someone who has traveled to a country with COVID-19 OR with someone who has shown symptoms of COVID-19 OR has a history of exposure to confirmed COVID-19 patients. A PUI requires hospital admission and immediate professional healthcare.

According to the same DOH decision tool, a person under monitoring (PUM) is someone who does not show the known symptoms of COVID-19 as prescribed by health authorities BUT has had a history of travel to countries where there has been an outbreak of COVID-19 OR has come in close contact with someone who has traveled to a country with COVID-19 OR with someone who has shown symptoms of COVID-19 OR has a history of exposure to confirmed COVID-19 patients. A PUM would require self-quarantine and monitoring for 14 days.

Both PUIs and PUMs would require testing for COVID-19 as well as contact tracing which involves locating people who have had close contact with someone who has been exposed to an infectious disease like COVID-19.

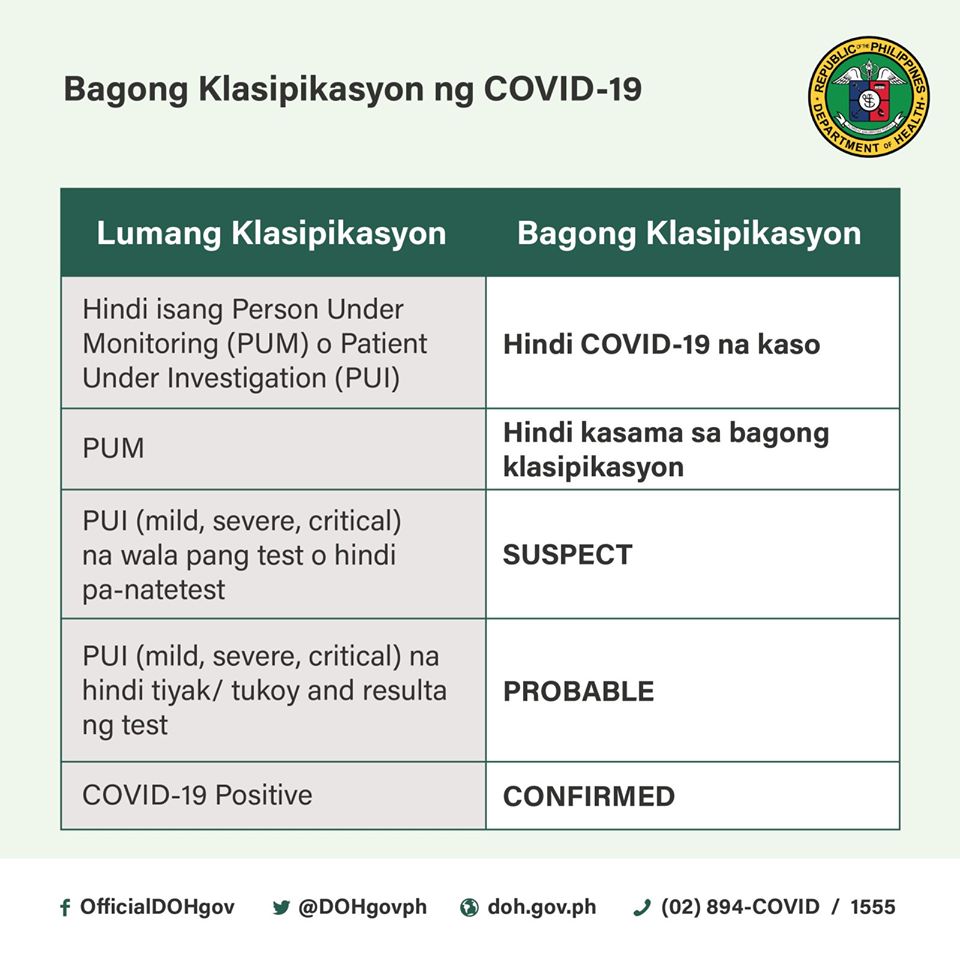

N.B. As of 11 April 2020, DOH issued a modified classification scheme for COVID-19 cases. PUMs are no longer included in the new classification, while PUIs (persons who exhibit any of the symptoms of COVID-19 from mild to severe to critical) are classified either as SUSPECT, PROBABLE, or CONFIRMED cases. SUSPECT cases are those who have yet to be tested for COVID-19. PROBABLE cases are those who have been tested but are still awaiting results. CONFIRMED cases are those found to be positive for COVID-19. DOH explains that this new lexicon is intended to provide a uniform reporting of data. This new classification does not change the spirit and intent of the Act to protect the welfare of all Filipinos in dealing with the COVID-19 emergency.

Back to Questions

10

What kind of standards and protocols does the Act provide for in preventing or suppressing the further spread of COVID-19 in the Philippines?

Under the Act, the President is authorized to follow, adopt, and implement the guidelines and best practices of the World Health Organization (WHO) in dealing with COVID-19 specifically in the areas of education, detection, protection, and treatment.

In addition, the Act also authorizes the President to expedite and streamline the accreditation of testing kits as well as facilitate the prompt testing of PUIs and PUMs by both public and private healthcare institutions and provide for the immediate isolation and treatment of confirmed COVID-19 patients.

Back to Questions

11

Since this is a national health emergency, are health workers entitled to any benefits under the Act?

Yes. Under the Act, the President is authorized to ensure that public health workers are provided with a COVID-19 special risk allowance in addition to their hazard pay.

In the event of their exposure to COVID-19 or any work-related injury or disease experienced by public and private health workers for the duration of the emergency, PhilHealth is to be directed by the President to shoulder all their medical expenses.

The Act also provides that every public and private health worker who contracts severe COVID-19 infection while in the line of duty is to be provided with a one-time compensation in the amount of P100,000. [N.B.: The Act specifies that the infection be “severe” so those who show only mild symptoms or are asymptomatic may not qualify for this compensation.] The surviving families of public and private health workers who may die while fighting the COVID-19 pandemic are to be awarded P1 million compensation. Both forms of compensation for all health workers are to be applied retroactively from 1 February 2020.

12

What are the responsibilities of local governments under the Act?

Section 4 of the Act authorizes the President to ensure that all local governments act within the letter and spirit of and are cooperating fully with the directives and regulations of the national government specific to the implementation of the enhanced community quarantine to address the COVID-19 emergency. However, local governments are allowed to exercise autonomy “in matters undefined by the National Government” although the actions to be taken by local governments must still be within the parameters set by national authorities.

In order to effectively execute the terms of the enhanced community quarantine, local governments are also authorized by the Act to use more than 5% of their calamity funds subject to additional funding from the national government.

Back to Questions

13

What can the general public expect from the temporary emergency powers of the President under the Act?

The Act authorizes the President to provide a social amelioration package to those who are suffering the most from the enhanced community quarantine especially the poor and those with barely any resources or savings to draw from. This social amelioration package includes the following:

- Low-income households are to receive an emergency monthly subsidy (P5,000 to P8,000) depending on regional minimum wage rates and taking into account subsidies received from conditional cash transfer and rice subsidy programs. [N.B. The Act specifies that this emergency monthly subsidy is to be given to only “around 18 million low-income households.” ]

- An expanded Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) either in cash or in kind whichever is more practicable and implemented through the local governments or directly to households with no income or savings and households from the informal sector to allow them to purchase basic goods and food for the duration of the quarantine.

The President is also authorized to ensure the availability of credit to productive sectors in the countryside as well as incentives for businesses to manufacture and import critical or needed equipment against COVID-19 that is exempt from duties and taxes.

The Act also provides that the President ensures the availability of essential goods and services (including food and medicines) to the people by adopting reasonably necessary measures to facilitate the movement of such goods and services as well as minimize supply chain disruptions to the maximum extent possible. In order to ensure the speedy movement and distribution of such essential goods and services, the government is also to make sure that encroachments and other obstacles to traffic in all roads including illegal constructions in public places are removed.

The President is likewise authorized to move statutory deadlines and timelines for the filing of official documents, payment of taxes, and other fees required by law beyond the quarantine period.

In addition, banks and other financial institutions, both public and private, including GSIS, SSS, and Pag-ibig Fund are directed by the President to issue a 30-day extension for the payment of all loans (including those with multiple loans) as well as credit card payments falling due within the quarantine period without incurring interests, penalties or other charges. A similar 30-day extension is provided for the payment of residential rents falling due within the quarantine period.

Back to Questions

14

Are there other special temporary powers given to the President under the Act?

Yes. All special temporary powers to be exercised by the President as authorized in the Act are specified in Section 4. [N.B. The President can only exercise such powers for the duration of the existence of the national health emergency and only to deal with such emergency.]

When the public interest so requires, the Act authorizes the President to direct the operation of private establishments (hospitals, transports, etc.) to serve as quarantine areas or as medical relief and aid distribution locations or other temporary medical facilities including the transport of and temporary accommodations for health emergency personnel. The management of such private establishments are to be retained in the hands of their owners but the owners are required to provide a full accounting to the President of their operations (including additional costs and damages incurred) as the basis for their reasonable compensation.

The President has the power to take over the operations of private enterprises that refuse or signify that they are no longer capable of operating, subject to Constitutional limits and safeguards.

Likewise, the President is authorized to hire temporary health personnel to augment the current health workforce and provide them with government hazard duty pay.

The President is also authorized to enforce measures to protect the people from hoarding, profiteering, price manipulation, product deceptions, monopolies “or other pernicious practices” that affect the supply, distribution and movement of food, clothing, hygiene and sanitation products, medicine and medical supplies, fuels, and other articles of prime necessity, whether imported or locally produced or manufactured.

The Act provides for exemptions to the Government Procurement Reform Act and authorizes the President to expedite government procurement procedures for the duration of the national health emergency involving the following goods:

- Personal protective equipment (e.g., gowns, masks, goggles, face shields, etc.), surgical equipment, medical equipment, medical supplies and consumables such as alcohol, sanitizers, tissue, thermometers, common medicines, testing kits, and other health-related supplies as may be determined by the Department of Health (DOH). Such goods are to be allocated and distributed to local public health facilities (such as, but not limited to the UP-PGH, Lung Center of the Philippines, and Dr. Jose N. Rodriguez Memorial Hospital); private hospitals with existing capacity to provide care and treatment to COVID-19 patients; and public and private laboratories with existing capacity to test suspected COVID-19 patients.

- Goods and services for social amelioration in affected communities

- Lease of real properties for use to house health workers or serve as quarantine centers, medical relief stations or temporary medical facilities

- The establishment, construction, and operation of temporary medical facilities

- Utilities, telecommunications and other critical services related to the operation of quarantine centers, medical relief stations or temporary medical facilities

- Providing for other related (ancillary) services

The President is also given the power to temporarily require businesses to prioritize and accept contracts for materials and services necessary in the fight against COVID-19 subject to fair and reasonable terms. The President can also regulate and limit the operation of all transportation (land, sea, and air), whether private or public in a manner that will allow the government to address the COVID-19 health emergency.

The President also has the special power to authorize alternative working arrangements for employees and workers in government as well as the private sector to conform with the enhanced community quarantine and other measures to address the COVID-19 national health emergency.

The President is also authorized by the Act to undertake measures to conserve and regulate the distribution and use of power, fuel, energy, and water to ensure an adequate supply of such necessities for the duration of the national health emergency.

Back to Questions

15

Does the Act allow the president to change anything in the 2020 national government budget?

Yes. The Act temporarily authorizes the President to reprogram, reallocate, and realign savings from the 2020 budget as may be necessary to address the COVID-19 emergency like allocating additional funds for social amelioration, recovery areas, and assistance to sectors and industries affected. Such reallocation shall be deemed automatically appropriated as per this Act for the duration of its effectivity. In addition, the President can also temporarily allocate funds held by GOCCs or any national government agency to address the COVID-19 emergency.

[N.B. The President can also realign savings from the 2019 national budget. RA 11464 provides for the extension of the availability of the 2019 appropriation up to 31 December 2020.]

Back to Questions

16

What happens to the other government-appropriated projects and programs that do not pertain to dealing with the COVID-19 emergency?

Under the Act, the President can temporarily discontinue appropriated programs and projects of government in order to utilize the generated savings to address the COVID-19 emergency prioritizing funds to the operational budgets of DOH, PGH, the National Disaster Risk Reduction Fund, programs of DOLE for displaced / disadvantaged workers, DTI livelihood seeding programs, DepEd School-based feeding programs, DSWD programs, LGU allocations, and other quick response funds allocated to different government agencies. Discontinued programs may be revived after the national health emergency has passed within the next two fiscal years.

Back to Questions

17

Does the Act allow for donations of health products?

Yes. The Act allows donations to be made to the government’s efforts to address the COVID-19 emergency. The President is authorized under the Act to make sure that donations of health products and their distribution to their intended recipients are not unnecessarily delayed provided that such health products are duly certified by the appropriate regulatory agency or clearance from an accredited third party from countries with established regulations. This does not apply to health products that do not require clearance or certification from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The President is also authorized to partner with the Philippine Red Cross as the primary humanitarian agency in giving aid to the people specific to the distribution of goods and services incidental to the fight against COVID-19 subject to reimbursement.

Back to Questions

18

To whom is the President accountable under the Act?

The Act was promulgated by virtue of a legislative act of Congress granting special emergency powers to the President. As such, the President is to make an accounting to Congress of all actions taken by the Executive Branch of government throughout the declared national health emergency.

Section 5 of the Act requires the President to submit a weekly report to Congress of all acts performed during the immediately preceding week that includes the amount and utilization of funds pursuant to addressing the COVID-19 emergency.

Back to Questions

19

Does the Act provide for an oversight mechanism?

Yes. Section 5 establishes a Congressional Oversight Committee to determine which acts, orders, rules, and regulations are within the restrictions provided in the Act. This Oversight Committee is composed of four members coming from each House appointed by the Senate President and House Speaker, respectively

Back to Questions

20

Can the Act supersede any existing law or regulation?

Yes and No. Section 7 states that in the event that the powers granted by the Act are in conflict with other statutes, orders, rules or regulations, the provisions of the Act will prevail for the time being. This can include laws pertaining to government procurements and the hiring of temporary public health personnel, among others. [N.B. The Act is in full force and effect only temporarily so whatever laws it supersedes will also be temporary.]

Section 8 also specifies that if any provision of the Act or its application is declared invalid, the remaining provisions and their application “to any other person or circumstance” will remain valid and in effect.

Back to Questions

21

Does the declaration of a health emergency invalidate the Constitution or any of its provisions?

No. The Constitution continues to be in effect. The Act provides that “nothing herein shall be construed as an impairment, restriction or modification of the provisions of the constitution” (Section 7) which includes the Bill of Rights and other constitutional guarantees.

Back to Questions

22

Does the Act punish those who violate its provisions?

Yes. Violations of the Act are punishable with either imprisonment of two months or a fine of not less than P10,000 but not more than P1 million or both, “at the discretion of the court” (Section 6).

If the offense is committed by a corporation or any other juridical person, the penalty is to be imposed on the president, directors, managing partners who participated in the commission of the offense or who allowed it to be committed or failed to prevent its commission.

If the offender is a public official or government employee, the person can be meted the additional punishment of perpetual or temporary absolute disqualification from office.

Back to Questions

23

What offenses are punishable under the Act?

Section 9 states that the Act is in full force and effect only for the duration of the national health emergency (see above). Hence, it is important to point out that these offenses are in effect only for the duration of the national health emergency.

Section 6 enumerates the offenses under the Act as follows:

- LGU officials disobeying quarantine policies or directives set by the national government in response to the COVID-19 emergency (N.B. Local government violations should not include political or ideological differences or disagreements with the national government or any individual member thereof.)

- Private establishments (hospitals, medical and health facilities, passenger vessels, etc.) that unjustifiably refuse to operate as directed by the President

- Engaging in hoarding, profiteering, price manipulation, product deceptions, monopolies “or other pernicious practices” that affect the supply, distribution and movement of food, clothing, hygiene and sanitation products, medicine and medical supplies, fuels, and other articles of prime necessity, whether imported or locally produced or manufactured

- Refusal to prioritize or accept contracts for materials and services necessary for the quarantine

- Refusal to provide a 30-day extension for the payment of all loans and rents without incurring interests, penalties, fees, or other charges

- Failure to comply with reasonable limitations on the operations of transport (land, sea, and air) sectors, public or private

- Impeding access to roads, streets and bridges as well as putting up prohibited encroachments or obstacles and illegal constructions in public places where they have been ordered to be removed

- all other acts punishable under existing laws

Back to Questions

24

Is spreading false information also an offense punishable under the Act?

Yes and No. Several conditions need to be present. The Act punishes (a) individuals or groups (b) creating, perpetuating, and spreading (c) false information (d) regarding the COVID-19 crisis (e) on social media and other platforms and that (f) such information would have “no valid or beneficial effect on the population, and (g) are clearly geared to promote chaos, panic, anarchy, fear, or confusion” (see Section 6(f)). Other punishable acts also include the use of scams, phishing, fraudulent emails, or other similar acts.

The above is in addition to the punishable cybercrime offenses enumerated in the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 (RA 10175). The Revised Penal Code also punishes “any person who by means of printing, lithography, or any other means of publication shall publish or cause to be published as news any false news which may endanger the public order, or cause damage to the interest or credit of the State” or utterances that cause disobedience to the law or constituted authorities “or extol any act punished by law” (Article 154).

[N.B. Although the Act does not define it, false information can be defined as information that is established to be patently untrue. However, merely creating or disseminating false information per se would not be enough to be considered an offense under the Act.]

Back to Questions

25

What constitutes the elements of chaos, panic, anarchy, fear, and confusion associated with spreading false information under the Act?

The Act does not prescribe the specific and concrete elements of chaos, panic, anarchy, fear, and confusion which, while obvious and commonsensical, can have the potential to be subjectively and summarily determined and applied especially during times of emergencies. At the same time, the act of spreading false information can also be misconstrued as openly criticizing government and interpreted as one that is punishable under the Act especially if such criticisms lead to feelings of fear, panic, chaos, or confusion on the part only of certain groups or individuals but not in everyone.

Back to Questions

26

Are my Constitutional rights still protected then?

Yes. Under Section 4(ee) of the Act, the public is assured that all other measures undertaken by the government to respond to the COVID-19 emergency would be subject to the Bill of Rights and other constitutional guarantees.

The Act does not suspend the writ of habeas corpus. Nor does it suspend the basic rights that everyone is entitled to under the 1987 Constitution, most notable of which is the right to due process. The current health emergency warrants only the imposition of certain restrictions on the free movement and physical assembly of individuals subject to the quarantine guidelines enforced by the authorities. Likewise, physical distancing and the wearing of face masks have now become mandatory in public spaces.

Back to Questions

Download the FULL TEXT of the primer HERE.

About the Primer: This primer was prepared by Professor Jorge Tigno with inputs from other faculty members of the Department of Political Science, University of the Philippines, Diliman. It hopes to provide basic information related to the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act of 2020 and encourage the readers to discuss the issues surrounding the law and its implementation.

This is part of the information campaign of the UP sa Halalan project of the Department of Political Science.